Public executions in the 19th century -Rome-

"Viengheno: attenti: la funzione è llesta..."

"Viengheno: attenti: la funzione è llesta..."(Here they come: pay attention: the ceremony is short...)

These are the opening words of one of several sonnets by the famous dialect poet G. G. Belli inspired by executions that took place in Rome.When the city was ruled by the papal authority, the so-called 'Pope King', up to 1870, public executions were one of the common people's favourite happenings, attended by crowds, who found this unholy practice not only amusing, but even took their sons to witness the event for educational purposes, on the very moment the blade fell down, they used to give the kid a slap, as a tangible reminder of what one day might have been their own fate if they had got into trouble with justice!From 1796 to 1864 the protagonist of these frequent executions in Rome was: Giovanni Battista Bugatti, whose nickname Mastro Titta, became legendary and a synonym for 'executioner': during his 70-year long activity, he performed 516 executions, or justices, as they used to be called.

Although he professed one of the most outrageous activities,

Mastro Titta carried out his duty with a certain detachment, a traditional roman attitude towards ill fate. He is even known to have sometimes offered the condemned a last pinch of snuff (see the photo above), almost as to say don't blame me for being here today, or cheer up: it won't take long, I'll do a neat job!!

Mastro Titta lived on an official job: he was an 'umbrella-painter', an activity for which he ran a shop next to his house in Borgo district, on the western side of the river Tiber, next to the Vatican, where via degli Ombrellari (umbrella-makers street) still exists today. Due to his other more occasional 'work', for the sake of his own safety, he was not allowed to enter the city's central districts (i.e. on the opposite side of the Tiber), except officially, for the well-known reason and so on every crucial day he wore his scarlet cloak and

'cross the bridge', this meant that somebody was going to lose his head very soon….

Public executions used to be held on fixed spots, one of these was the small square at one end of the bridge in front of Sant'Angelo Castle, whose charming view was still not enough to deaden the cruel show it used to host.

Another place was piazza del Popolo. Still today, a plaque set in 1909 by a democratic association remembers two patriots sentenced here in 1825, their capital punishment being ordered by the pope, without evidence. The story of the two patriots also inspired movie director Luigi Magni for the making of one of his best known titles, The Conspirators (original title:

Nell'anno del Signore, 1969).

Another typical feature of the gloomy cerimony was the procession of friars who accompanied the condemned up to the scaffold, wearing a black cowl with a pointed hood.They belonged to the Confraternita della Misericordia, "Brotherhood of Mercy", a centuries-old congregation founded in Florence. Their see in Rome was by the church of

San Giovanni Decollato ("St.John Beheaded", i.e. St.John the Baptist), located in a narrow street by via dei Cerchi, another spot where executions took place in the 1700s and 1800s.

The congregation was in charge of delivering religious consolation to the condemned; after the execution, the same friars also carried away the corpses to the church's cloister, where they buried them.By an ancient privilege, granted by pope Paul III in 1540, each year the Brotherhood of Mercy had the right of freeing one convict sentenced to death: the choice was carried out by gathering information about the several prisoners, about their crimes and their trials, by asking the victims' families for forgiveness (the convict could not be freed without their permission), and by finally holding a ballot among the members, to choose which prisoner was more worthy of being saved, and when to hold the ceremony. On the given day, a procession of friars would march up to the jail, where the chosen prisonery would be officially handed over to them. The congregation would have then found the man an honest job or, in the case of a stranger, would have given him some money to travel back home.

(Symbol of the congregation, a head on a plate)

(Symbol of the congregation, a head on a plate)Memories of the aforesaid rituals and ceremonies are now kept in the congregation's Historic Chamber, by St.John's church, open to the public once a year, on June 24, the saint's own day.

What is left of

Mastro Titta, instead, besides his legendary fame, is the scarlet cloak that the executioner used to wear on official occasions, when he was allowed to 'cross the bridge'; it is now on display in

Rome's Criminology Museum.

The “Madonna del Carmelo”, in Rome, has assumed, in the years, several peculiar connotations becoming, around 1920, the festivity of “de noantri” (noantri, in roman dialect, means “we other” referring to people who live in Trastevere district regarding those who live, instead, on the opposite side of Tiber river!!). A legend tells that some fishermen, fishing on the Tiber river towards the half of July of a no-well known year, collected, from the river, a case which in the inside hidden one precious statue of the Madonna.

The “Madonna del Carmelo”, in Rome, has assumed, in the years, several peculiar connotations becoming, around 1920, the festivity of “de noantri” (noantri, in roman dialect, means “we other” referring to people who live in Trastevere district regarding those who live, instead, on the opposite side of Tiber river!!). A legend tells that some fishermen, fishing on the Tiber river towards the half of July of a no-well known year, collected, from the river, a case which in the inside hidden one precious statue of the Madonna. The fishermen, delighted by the beauty of the Vergine, hurried to transfer it in the sant'Agata church where still today she is. From that day, about on the third Sunday of july the Madonna goes on procession from San’Agata church through all the alleyways of Trastevere in order to reach saint Crisogno church, where she stays for eight days at the end of which she comes back to sant'Agata.

The fishermen, delighted by the beauty of the Vergine, hurried to transfer it in the sant'Agata church where still today she is. From that day, about on the third Sunday of july the Madonna goes on procession from San’Agata church through all the alleyways of Trastevere in order to reach saint Crisogno church, where she stays for eight days at the end of which she comes back to sant'Agata. The procession was anciently organized by the company of the "vascellari", the potters, but today it’s a task of the “confratelli della Arciconfraternita del Ss. Sacramento e Santa Maria del Carmine”, who, with their white traditional frock, carry the statue throughout Trastevere.

The procession was anciently organized by the company of the "vascellari", the potters, but today it’s a task of the “confratelli della Arciconfraternita del Ss. Sacramento e Santa Maria del Carmine”, who, with their white traditional frock, carry the statue throughout Trastevere. This celebration, a time characterized by the presence of the "vascellari" with their jug overflow of wine, is today characterized by the pagan festivity called festivity of “noantri”.

This celebration, a time characterized by the presence of the "vascellari" with their jug overflow of wine, is today characterized by the pagan festivity called festivity of “noantri”.  During these days all people of Trastevere stand to this public party in a climate of common joy with open taverns, manifestations, wondering theatres and open markets. For a week Trastevere become like a small village with all tourists surprised by the caos and confusion and often unware on what is the Christian recurrence.... remember always: FESTA DEI NOANTRI la festa dei Trasteverini!!

During these days all people of Trastevere stand to this public party in a climate of common joy with open taverns, manifestations, wondering theatres and open markets. For a week Trastevere become like a small village with all tourists surprised by the caos and confusion and often unware on what is the Christian recurrence.... remember always: FESTA DEI NOANTRI la festa dei Trasteverini!!

Look at the animal who is carrying the obelisk, may you seen something like a piggy?!

Look at the animal who is carrying the obelisk, may you seen something like a piggy?!

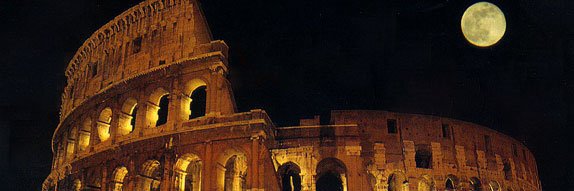

The "Anphitheatrum Flavium" was built by the Emperor Vespasiano in the 72 d.c. According to the most known legend the name Colosseo came from the enormous statue, called the “Colosso di Nerone” (more than 35 meters high!), built near the Anphitheatrum Flavium and representing the Emperor Nerone. Nowdays there is a modern base made in "tufo" at the entrance of the metro line A Colosseo reminding us the original position of the ancient Colosso. This picture would be an ideal re-construction of the Colosso di Nerone (if you want to have the exact chronology of the Colosseo

The "Anphitheatrum Flavium" was built by the Emperor Vespasiano in the 72 d.c. According to the most known legend the name Colosseo came from the enormous statue, called the “Colosso di Nerone” (more than 35 meters high!), built near the Anphitheatrum Flavium and representing the Emperor Nerone. Nowdays there is a modern base made in "tufo" at the entrance of the metro line A Colosseo reminding us the original position of the ancient Colosso. This picture would be an ideal re-construction of the Colosso di Nerone (if you want to have the exact chronology of the Colosseo